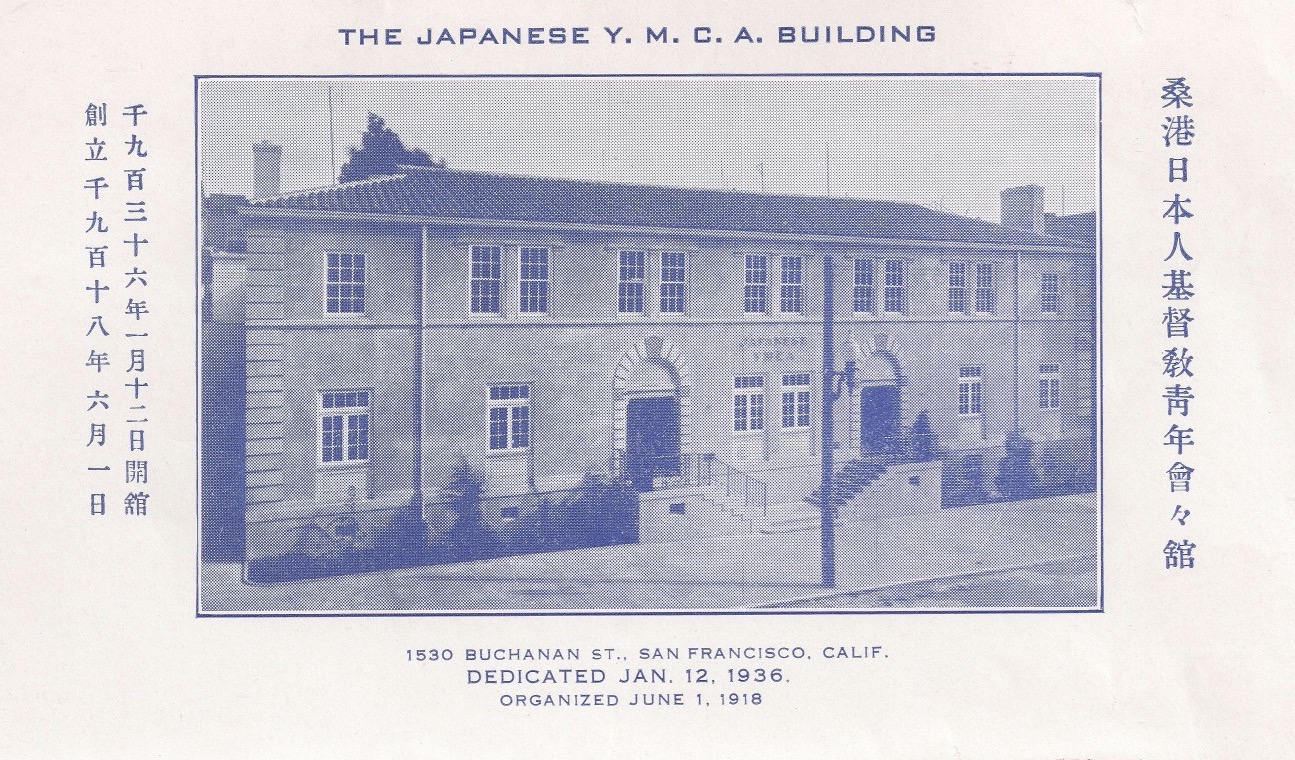

Japanese YMCA (Buchanan YMCA) and Relocation Centers during WWII.

The attack on Pearl Harbor changed the trajectory of Asian communities across the states, the majority of whom resided on the West Coast. In Japantown, San Francisco lives drastically changed within months of the Pearl Harbor Naval Base bombings.

Following the attack, laws were enacted to target Asian communities.

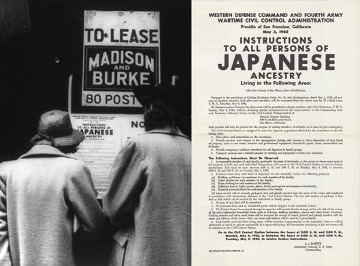

Executive Order 9066

Issued by President Franklin Roosevelt on February 19, 1942, this order authorized the evacuation of all persons deemed a threat to national security from the West Coast to relocation centers further inland.

WCCA - Wartime Civil Control Administration

The WCCA was an agency established on March 11, 1942, by General Order No. 35 issued by General John DeWitt , head of the Western Defense Command, "[t]o provide for the evacuation of all persons of Japanese ancestry from Military Area No. 1 and the California portion of Military Area No. 2 of the Pacific Coast with a minimum of economic and social dislocation, a minimum use of military personnel and maximum speed; and initially to employ all appropriate means to encourage voluntary migration." [1] Karl Bendetsen , who had played a key role in the promulgation of Executive Order 9066 that authorized the mass removal, was named the commanding officer of the WCCA and was also promoted to colonel the following day at the age of thirty-four.

* WCCA oversaw the forced removal of roughly 120,000 Japanese Americans from the West Coast and administered detention camps called “temporary assembly centers.”

These laws made community organizations, like the YMCA, centers for updating the latest information, centralize ways to communicate with the community, and even implement new laws such as registering Japanese families and facilitating their removal.

Japantown in the Bay

The Bay Area holds a rich history of Asian communities from across the globe for some generations prior to the Pearl Harbor bombing. Chinese workers came to help construct the Transcontinental Railroad in the 1840s, about 20,000 Chinese migrants made the Bay and made it their home. Prior to the San Francisco Japantown we know today, the South of Market (SoMA District) was established as an immigrant and working-class area, drawing in waves of Japanese immigrants by the 1880s. This area was the first to be called Nihonjin-Machi, or Japanese People Town, by its inhabitants—a different meaning than the term used by outsiders, Nihonmachi, which translates directly to Japantown. However, after the 1906 earthquake and its succeeding fires, the South of Market area was destroyed, leading to the relocation of Japantown to Western Addition.

The community thrived at Japanese YMCA. This was a space where they could come together.

By the time the Pearl Harbor attacks happened, many Asian Americans had no choice and were forcibly removed from their homes to be relocated to internment camps while others were arrested without evidence and transferred to prison camps. Before arriving at the internment camps, they were first brought to transition facilities.

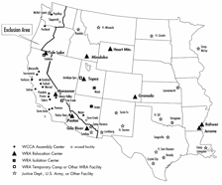

Transition Camp Tanforan (Detention Facility) - San Bruno

April 29, 1942 was the first day of evacuation from Japantown. People were allowed to pack very few of their personal items. Their first stop was the Civil Control Station, where people were registered before being sent to the Tanforan Assembly Center via bus. Tanforan in San Bruno, located 12 miles (19.3 kilometers) south of San Francisco, was one of 17 “civilian assembly centers” created to temporarily detain Japanese Americans for up to six months. From April 28 to October 13, 1942, 7,816 people were held at Tanforan, making it the second largest assembly center. After leaving Tanforan, most of the Japanese were incarcerated at the Topaz Internment Camp in Utah from 1943 to 1945.

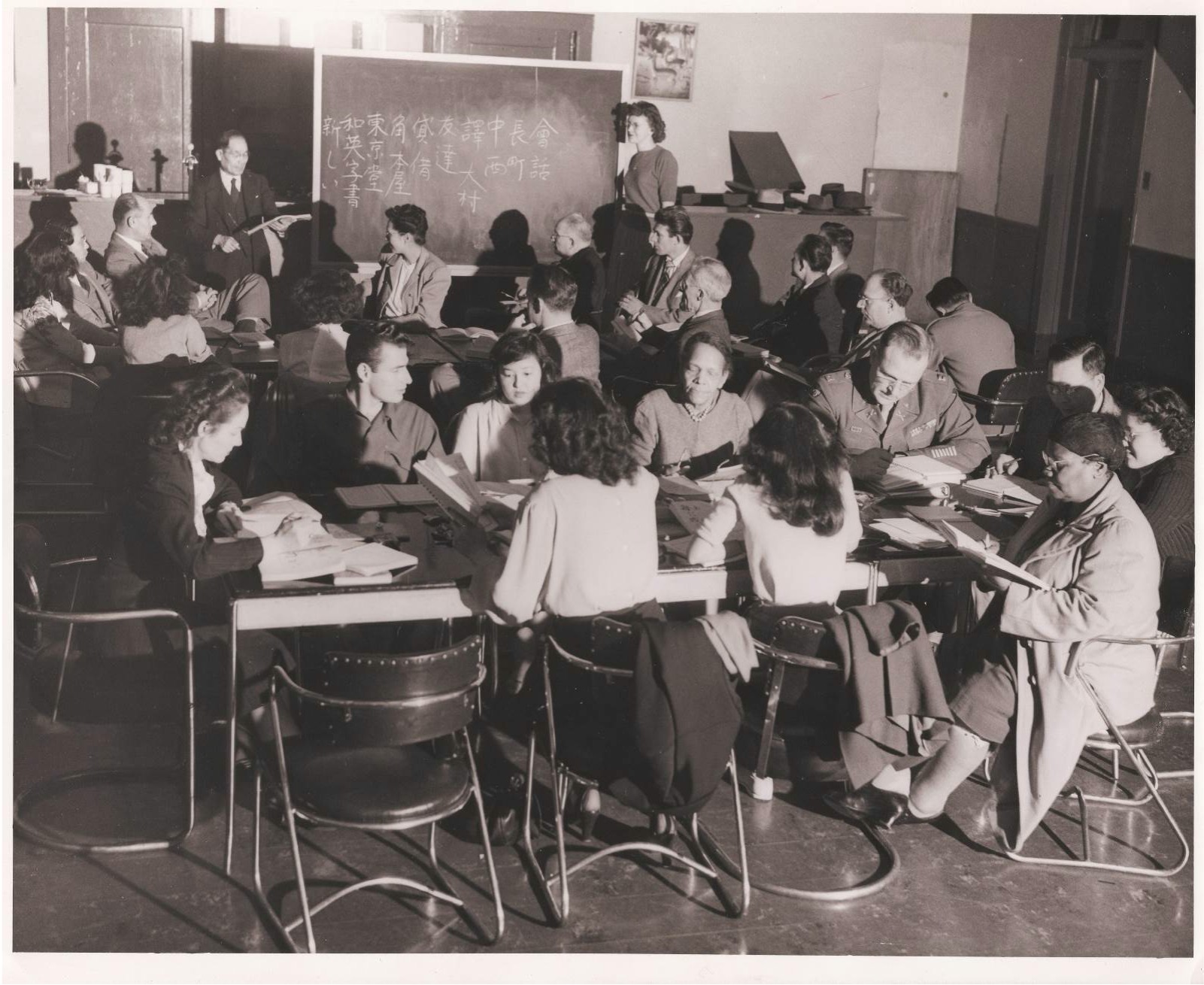

Japanese YMCA Registers Japanese Families

Japanese YMCA was a community space for many Japanese American families; however, when the new laws were enacted, all Japanese Americans were required to register prior to the internment camps. These were mandates the YMCA had to follow, as everyone did city and nationwide. This image shows families registering at the YMCA before being relocated. With the community removed from Japantown, the space was turned over to the United Service Organizations (USO) to entertain and serve soldiers of color (many Black soldiers).

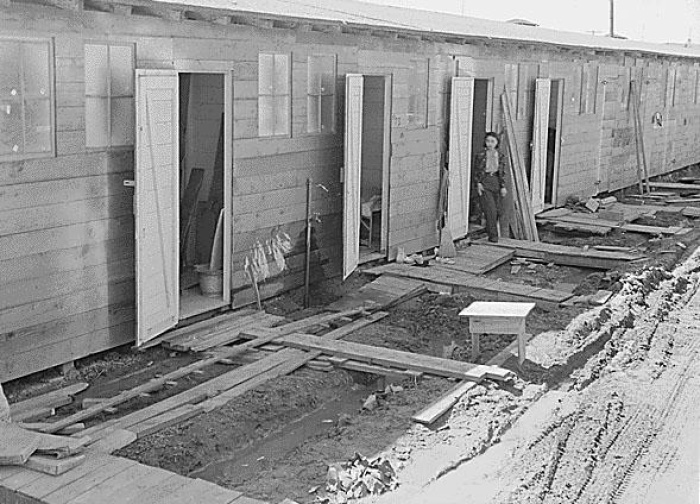

Families Placed in Camps

These internment camps were called “relocation centers” that typically included some form of barracks with communal eating areas. Several Japanese American families would be housed together. Each camp was its own “town” that had schools, post offices and work facilities as well as farmland for growing food and keeping livestock. Violence and riots would occur as tensions grew, often as a result of insufficient rations and overcrowding.

The prison camps ended in 1945 following the Supreme Court decision, Ex parte Mitsuye Endo. In this case, justices ruled unanimously that the War Relocation Authority “has no authority to subject citizens who are concededly loyal to its leave procedure.”

Tanforan Assembly Center placed some families in horse stables as they awaited relocation. While these families worked together in these desolate spaces, many resisted as much as they could. Children were born and raised in these camps. People got married in these camps, and although they were interned, Japanese Americans still voted as it is their civic duty.

Eventually the Japanese Are Released

Eventually, the Japanese are released and return to Japanese YMCA and remains an important part of the community.

After WWII, in 1946, the USO turned the building back over to YMCA and was renamed the Buchanan YMCA after the street it was located on. The staff quickly set out to serve the needs of the returning Japanese and African American population. Fred Hoshiyama was called to the Buchanan YMCA to work with the community as well as an African American program director, Harry Payne to inaugurate an interracial program between African and Japanese Americans to meet the needs of the youth in the community.

For more information about this subject watch Now This Video about these camps. Diary Reveals Reality of Living in a WWII Japanese Internment Camp | NowThis